\The Elements: Line

A line is a mark made by a moving point and having psychological impact according

to its direction, weight, and the variations in its direction and weight. It

is an enormously useful and versatile graphic device that is made to function

in

both visual and verbal ways. It can act as as a symbolic

language, or it can communicate emotion through its character and direction

Line is not necessarily an artificial creation of the artist or designer; it

exists in

nature as a structural feature such as branches, or as surface

design, such as striping on a tiger or a seashell.

It can function

independently to suggest forms that can be recognized,

even when the lines are limited in extent. This can be seen in drawings such as the Saul Steinberg illustration shown here,

or in

Alexander Calder's minimal wire sculptures, which convey a great deal of

information about the figure with the most limited line.

Lines can be

combined with other lines to create

textures and patterns.

This is common in engravings and pen and ink drawings such as the one on

the right (click and enlarge to see linear detail). The use of line in

combination results in the development of

form and

value, which

are other elements of design.

However, line is not always explicit. It can exist

by implication, as the

edge of forms. As young children we usually begin drawing landscapes by making

outlines for earth, sky, and other objects. Gradually we learn that objects do

not have such outlines and we let color changes define the edges of shapes, creating implicit lines.

Thus we can speak of a horizon "line," or the "lines" of a car or a fashion

silhouette, even though we know there is no literal line present. For additional visual examples of

Expressive Qualities of Line

Certain arrangements of line are commonly understood to carry certain kinds of information.

For example,

calligraphy is recognizable as a representation of

words, even when we do not know the language. Calligraphic imagery is often

used by modern artists simply because of the mysterious messages implied in the

"code" of unknown language.

Line in the form of

maps is readily recognized as a symbolic

representation of a place. The place may be a local neighborhood, or the entire

world. It may be a carefully measured representation, or a stylized diagram,

such as a subway map. In either case, we understand it to be a device by which

we can understand the relationship between places; how to get from "here" to

"there."

Floor plans

Floor plans are a specialized kind of map, a commonly

understood device which describes a building. This linear language can

be understood even when the building is as unusual as this one, which

was to be constructed of a sprayed foam material in a decidedly

unconventional form.

Graphs

Graphs are another readily recognizable linear device. They are widely

used to communicate quantitative information and relationships in a visual way.

From the time we first meet them in basic algebra, to the last time we picked

up a copy of

USA Today, we encounter and interpret graphs.

Line also communicates emotion and states of mind through its character and

direction. The variations of meaning generally relate to our bodily

experience of line and direction.

Horizontal

Horizontal line suggests a feeling of rest or repose.

Objects parallel to

the earth are at rest in relation to gravity. Therefore compositions in

which

horizontal lines dominate tend to be quiet and restful in feeling. One

of the hallmarks of Frank Lloyd Wright's architectural style is its use

of strong horizontal elements which stress the relationship of the

structure to the land.

Vertical

Vertical lines communicate a feeling of loftiness and spirituality.

Erect lines seem to extend upwards beyond human reach, toward the sky. They

often dominate public architecture, from cathedrals to corporate headquarters.

Extended perpendicular lines suggest an overpowering grandeur, beyond ordinary

human measure.

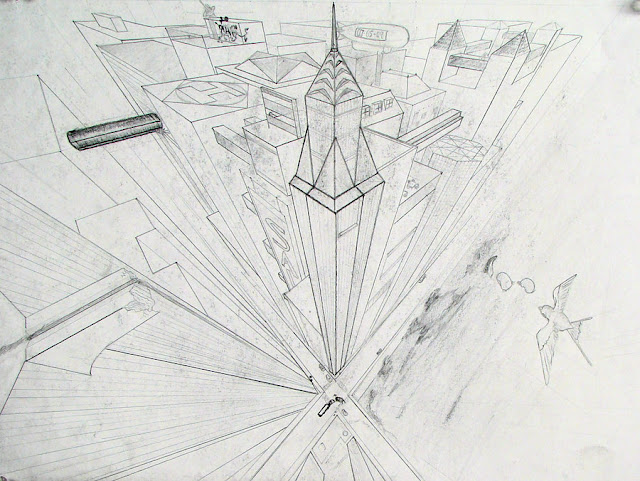

Diagonal lines

Diagonal lines suggest a feeling of movement or

direction. Since objects in a diagonal position are unstable in relation

to gravity, being neither

vertical nor horizontal, they are either about to fall, or are already

in

motion, as is certainly the case for this group of dancers. In a two

dimensional composition diagonal lines are also used to indicate depth,

an illusion of perspective that pulls the viewer into the

picture-creating an illusion of a space that one could move about

within. Thus if a feeling of movement or speed

is desired, or a feeling of activity, diagonal lines can be used.

Horizontal and vertical lines in combination

Horizontal and vertical lines in combination communicate

stability and

solidity. Rectilinear forms stay put in relation to gravity, and are not

likely

to tip over. This stability suggests permanence, reliability and safety.

In the case of the man in this family group, the lines seem to imply

stability to the point of stodginess.

Deep, acute curves, on the other hand, suggest

confusion, turbulence, even frenzy, as in the violence of waves in a

storm, the chaos of a

tangled thread, or the turmoil of lines suggested by the forms of a

crowd. The complicated curves used to form the mother in the family

group shown above suggest a fussy, frivolous personality.

Curved lines

Curved lines do vary in meaning, however.

Soft, shallow curves

suggest comfort, safety, familiarity, relaxation. They recall the

curves of the human body, and therefore have a pleasing, sensual

quality.

The

quality of the line is in itself a fundamental visual language,

to an extent that cannot be claimed for any other single element. Its use is

so universal that we are all profoundly sensitive to it. Even without an artist's

training, we can extract considerable meaning from the kind of line used in

a drawing. It is possible to recognize the soft, irregular lines of a quick

sketch from life, as seen in this study of a lion.

On the other hand, the crisp, carefully placed lines of the rhinocerous

are typical of a more studied, scrupulously worked studio drawing. The

lines suggest that this was not drawn from life, but from hearsay. This

is also evident from the fact that Durer drew this rather inaccurate

image in fifteenth century Europe when he could only have known of this

African animal from travellers' tales.

The quality of line in itself contributes to the mood of the work, and

for the master artist, the quality of line is a fundamental

expression of his/her style. This drawing of a nude by Matisse

demonstrates his ability to create his image through a minimal

number of expertly placed lines-lines that by their placement and

movement on the page identify this work with this artist as

surely as a signature.

For additional examples of how line works in design, follow this link.